The Affordable Care Act, building on decades of prior law, took important steps to establish a comprehensive regulatory structure that sets minimum standards for health care coverage. Despite those achievements, it remains possible for Americans to become enrolled in plans that do not meet the standards articulated in the ACA. This analysis explores these gaps in regulation and describes what can be done to close them.

We define good health care coverage as a plan that reflects three key attributes: it (1) covers a comprehensive array of health care services without regard to individuals’ pre-existing conditions, (2) has a benefit design that ensures consumers must bear only a reasonable share of health care costs, and (3) is offered by a financially solvent entity within a stable system for pooling risk. Federal law attempts to achieve these objectives, in partnership with state insurance regulators, by regulating the benefits that employers provide to their employees and the insurance products that carriers sell to individual consumers.

Health plans that don’t meet these standards are problematic for two reasons. First, consumers enrolled in such plans can face catastrophic financial risk if they have a significant health care need and may find their insurance of limited value. This is a particularly acute problem in market segments that use “post-claims underwriting” to exclude coverage for pre-existing conditions, since it makes it very difficult for consumers to evaluate coverage before enrolling. Second, non-compliant plans can use their low premiums to “cherry pick” healthy consumers away from broader and more regulated risk pools. This allows healthy individuals to access lower-cost plans (because they need not pool their risk with sicker people) but drives up costs for everyone that remains in the regulated market.

Gaps in the regulation of employer health coverage: There are three major gaps in federal regulation of employer health plans. The broadest and most significant is that while employer plans are subject to many regulatory standards, there is no provision in federal law that requires employer health plans to cover a comprehensive array of benefits. Most employers do provide a fairly comprehensive package in order to attract and retain employees, but even otherwise generous plans often exclude specific services or drugs. Further, the ACA’s employer mandate incentivizes employers to offer some form of coverage, even for low wage workers where a comprehensive benefit package is not economically viable, which leads to some employers offering extremely limited benefit packages. Indeed, some employers offer plans that cover only the ACA’s mandated preventive services, and no other benefits.

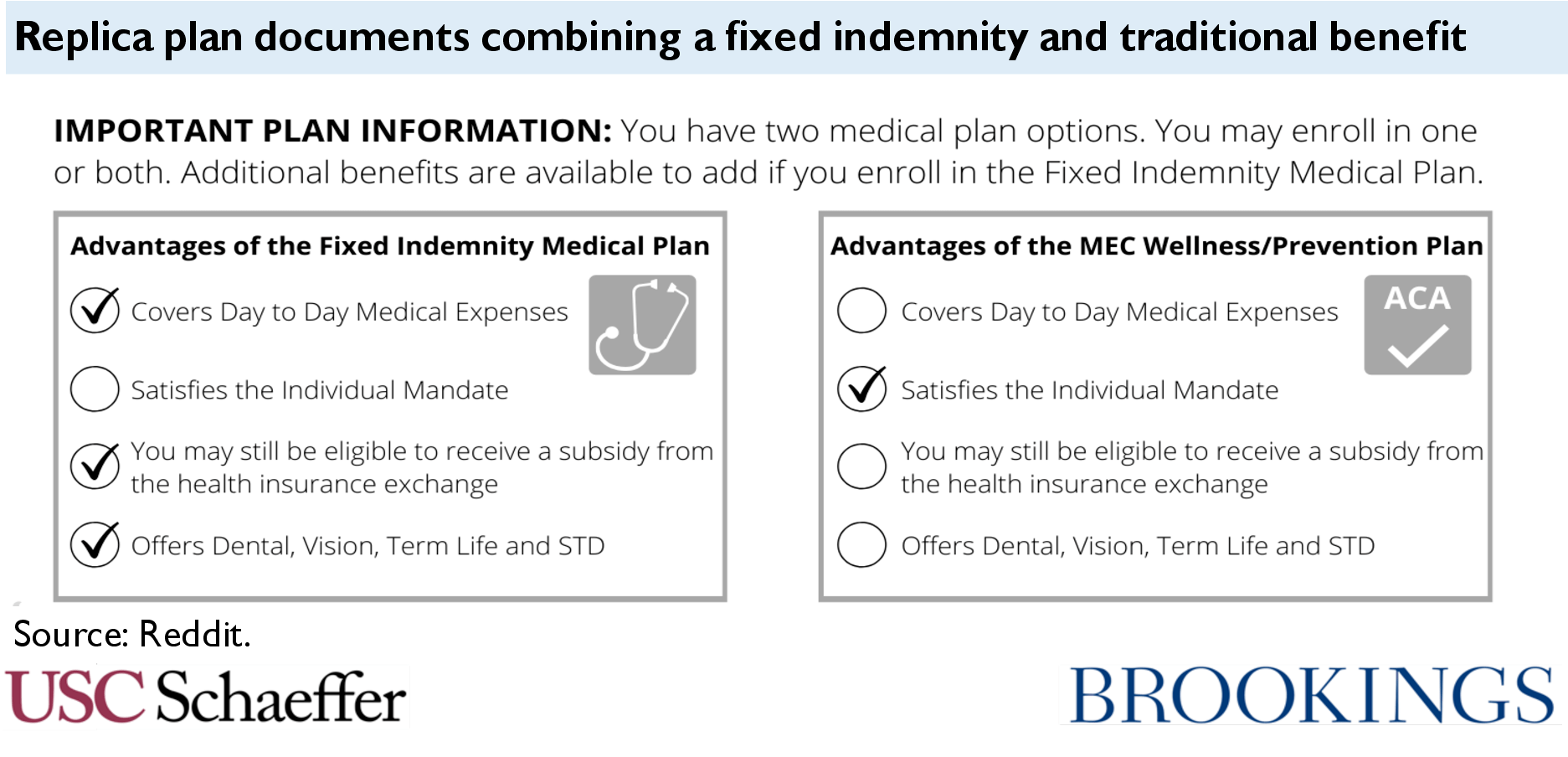

Second, federal law defines certain kinds of employer plans as “excepted benefits” and then exempts them from most federal regulation, even when they resemble a traditional plan. In particular, fixed indemnity plans are considered excepted benefits because they pay on a “per time period” basis, rather than paying based on actual medical costs incurred. But modern indemnity policies have developed detailed rubrics for payment, paying specific amounts “per day” an individual receives a particular health care service or “per month” they fill a prescription for a specific class of drugs. This benefit can come to look very much like regular health coverage, despite not being subject to otherwise applicable standards. While systematic data are not available, there is ample anecdotal evidence of employers offering the majority of their health care benefit through an unregulated fixed indemnity policy. A somewhat common approach appears to combine a very limited regulated plan (e.g. one covering only preventive services) with an excepted benefit fixed indemnity plan that offers all other benefits subject to various limitations and exclusions. Three other types of excepted benefits policies – accident, critical illness, and (to a lesser extent under current regulations) group supplemental coverage – could also serve the same function as fixed indemnity plans in this arrangement.

Finally, gaps in federal law enable small employers to avoid risk-pooling provisions that are generally intended to ensure pooling of risk across all small employers in a state. Small employers can leave the insurance market entirely by choosing to self-insure, and vendors across the country now sell “level-funding” plans that are stylized as a self-insurance arrangement with reinsurance coverage but in fact look very much like insurance. In addition, the federal government has attempted to facilitate small employers buying their coverage through “associations” that exclude them from the small group market, though some of those regulations have been enjoined by a federal court.

Gaps in the regulation of individual coverage: The market for individual coverage also features significant regulatory gaps. Plans that are subject to regulation are covered by a comprehensive scheme that satisfies the three criteria for “good” coverage described above; problems emerge from the many ways in which entities can offer coverage outside of that framework. The most familiar problem in the current market is short-term limited-duration plans. A provision in federal law exempts short-term plans from regulation but fails to define the phrase “short-term.” Current regulations take an expansive view, encompassing plans up to three years in duration. These plans can discriminate based on health status, exclude or cap major benefits, and impose very high cost-sharing, leaving consumers surprised by very large bills and pulling healthy enrollees from the regulated market.

Individual market regulation also provides an exemption for excepted benefits, which creates a similar loophole to that seen in employer coverage. New individual market fixed indemnity carriers offer benefit schedules with thousands of different payment amounts associated with receipt of specific medical services (with amounts paid directly to providers, just like standard health insurance). Even traditional carriers offer fixed indemnity benefits that pay on a highly detailed rubric, which varies with the severity of the hospitalization or outpatient service and the specific providers involved in care. Excepted benefits for accident and critical illness policies offer the same potential, and there is some evidence of misuse of accident policies. As with short-term plans, these types of excepted benefit policies discriminate against those with pre-existing conditions, leave consumers exposed to very high costs, and erode the regulated market’s risk pool.

Another gap arises because federal regulation of individual market benefits turns on what is considered “health insurance” under state law. A benefit that looks like health insurance and doesn’t fit into either of the regulatory exceptions described above can still be exempt from regulation if it is not considered a health insurance product that must be offered by a health insurance issuer under state law. Some states deliberately engineer exceptions from federal regulation in this way, using state law to classify health coverage offered by their state Farm Bureau as “not insurance.” Other exceptions arise more organically. When colleges and universities offer benefits to their students without involving an insurer, i.e. self-insured student health plans, the coverage is not considered insurance and therefore not regulated under state or federal law. Health-care sharing ministries also offer an unusual benefit structure that can often evade regulation, despite the fact that their benefit looks very much like traditional coverage and is not closely linked to shared religious beliefs or practices. Moreover, the challenges associated with these benefit forms have worsened since the ACA’s individual mandate penalty was reduced to $0. Just as these policies are considered “not insurance” for purposes of federal regulation, many of them were also considered “not insurance” under the mandate, thus deterring some uptake while the mandate remained in force.

So, what can be done? Policymakers can consider federal legislation, state legislative or regulatory action, or federal administrative tools that do not require new statutes.

Comprehensive federal legislation: Federal legislators could close each of the gaps described above. Specifically, comprehensive federal legislation would take six steps:

- Require employer health plans to cover essential health benefits at a minimum actuarial value. This will ensure that all employer health plans indeed offer a comprehensive benefit package.

- Redefine excepted benefits (in both the employer and individual markets) to reflect benefits that truly deserve exemption from federal law. Legislators should reshape the exemption for the types of supplemental coverage most prone to abuse by requiring a truly distinct policy form and by requiring that enrollees have another source of coverage of all EHB. They should also limit excepted benefits to plans that are not intended to duplicate, mimic, or supplant regulated benefits, to deter future attempts to evade regulation.

- End the exclusion of short-term limited-duration insurance from the definition of health insurance coverage. All plans should be subject to the same standards, regardless of contract length.

- Modify the federal definition of health insurance coverage and health insurance issuer to bring “not insurance” within the federal regulatory environment. Legislation could define all non-employer benefits or payments for medical care as insurance that must be offered by an issuer. This would require states to update their own legislation but would preserve full state control over risk bearing entities. Alternatively, federal law could allow “not insurance” to exist outside the state-federal regulatory partnership but nonetheless directly apply federal standards to these plans.

- Limit stop-loss coverage so that an employer arrangement will not be considered self-insurance unless the employer bears significant risk. Existing model legislation from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners could be updated and adapted to federal law.

- Codify provisions in federal regulations and guidance that can limit some forms of abuse, including standards related to association health plans and some limits related to insured student coverage.

This suite of reforms would generally ensure that any benefit that “looked like” health coverage was subject to minimum standards. On its own, while these policies would benefit many, they would also be expected to have negative impacts on some stakeholders, such as increasing costs for some employers, inducing other employers to drop health coverage rather than offer a comprehensive benefit, and increasing premiums for individuals who currently buy unregulated insurance. Other policy tools are available to mitigate those consequences, and indeed, they will be the result of any attempt to close gaps in the regulation of health benefits.

Options for states: In the absence of new federal legislation, there are important opportunities for states to take action to protect consumers and strengthen risk pooling:

- Limit the reach of short-term plans, either by prohibiting their sale, prohibiting pre-existing discrimination in short-term plans, or limiting them to just 3 months.

- Reign in problematic excepted benefit policies. States can bar the sale of fixed indemnity, accident, and critical illness policies that look too much like traditional health insurance. They can also impose a requirement that enrollees carry other coverage. And states can attempt to take enforcement action against the pairing of insured fixed indemnity plans with very skinny traditional employer plans as a violation of the prohibition on benefits that are coordinated with an exclusion.

- States should avoid enacting legislation authorizing Farm Bureau plans.

- Limit Health Care Sharing Ministries through legislative and enforcement tools. State laws that exempt HCSMs from regulation as insurance can be tightened or repealed, and states can take enforcement action against fraudulent HCSMs.

- Regulate self-insured student health plans and stop-loss coverage. States can require that colleges and universities offering self-funded benefits meet certain substantive standards, and they can prohibit stop-loss plans with very low attachment points.

- Regulate MEWAs to limit fraud and insolvency in this market segment.

- Oversee agent and broker conduct. States can place limits on the ways that licensed agents and brokers sell non-compliant forms of coverage.

Options for federal regulators: Finally, just as states have options in the absence of new federal legislation, so, too, does the federal government:

- Restrict short-term plans to less than 3 months. It would be straightforward for the federal government to reinstate 2016 regulations adopting this limited definition.

- Narrow the reach of fixed indemnity, critical illness, and accident excepted benefit policies by adopting a more detailed regulatory definition. While some regulatory approaches are foreclosed by a 2016 court decision, other options remain available. Specifically, regulators should require that these policies be structured in ways that distinguish them from health coverage, rather than allowing them to vary payments based on health care services.

- Define “licensed under state law” broadly in determining who is an issuer, limiting states’ ability to deliberately promote unregulated forms of “not insurance.” Specifically, the federal government could construe state authorization of Farm Bureau products as a form of state licensure, bringing the plans under the umbrella of existing law.

- Regulate the conduct of brokers subject to federal standards. Tens of thousands of agents and brokers, including major online vendors, receive an annual certification from the federal government or a state-based Marketplace that permits them to sell subsidized coverage through the federal or state Marketplace. These certifications could be limited to those who agree to limitations on the marketing and sale of non-compliant forms of coverage.

Within any given state, these tools have a more limited reach than the full toolbox available to state regulators, but of course would have national scope.

The full text of the paper is available here.

The author thanks Kathleen Hannick for superb research assistance and thoughtful feedback on this work. Brieanna Nicker and Spoorthi Kamepalli also provided valuable contributions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.