I enjoyed a chance to discuss “The Hollowing Out of US Democracy” at the Center for Economic and Social Research on April 19. My basic argument is that the decline of certain types of associations has left many Americans, especially White working-class citizens, in what my colleagues at the Tisch College of Civic Life and I call “Civic Deserts.” This trend does not explain why a Republican president won in 2016 or why he has taken certain views of policy and ideology. But it does explain the appeal of his leadership style. Citizens who have never belonged to everyday local associations with responsible and accountable leaders do not expect such leadership from their president.

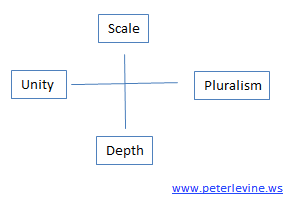

In my talk, I elaborated on the argument made here. I introduced my SPUD framework, which stands for Scale, Pluralism, Unity, and Depth. SPUD, I propose, is the recipe for effective civic and political organizations, but it is difficult to achieve and is much scarcer today than decades ago.

Scale is essential because organizations that are active in politics need numbers to win. Pluralism means a diversity of opinions and perspectives, without which groups are prone to adopt foolish or selfish goals and lose the support of the broader public. At the same time, groups must display unity to be taken seriously as a political force. And finally, they must transform their individual members. People don’t automatically begin with the concerns, interests, and skills necessary to be political actors. Good organizations develop those traits, which reflects depth.

SPUD is hard because plurality tends to conflict with unity, and scale with depth. Nevertheless, the great social movements have achieved all four. For example, the American Civil Rights Movement recruited many thousands, transformed individuals into powerful leaders, encompassed a wide range of social groups, types of organizations, and political agendas, and yet coalesced in displays of unity, such as the March on Washington in 1963.

Social movements move: they are about change. But stable associations, such as unions, grassroots political parties, religious denominations, and metropolitan daily newspapers, also require SPUD. I argue that they achieved SPUD 50 years ago, but all have badly lost scale.

As an example, a successful local newspaper achieves scale—in the form of a large subscriber base—by offering a package that includes sports, classified ads, and comics, yet it transforms some readers into active citizens by telling them what to care about on the front page. It also combines pluralism (on the editorial page and in the voices quoted in news articles) with unity by presenting the headline news in a certain way. No newspaper has ever been ideal, and we can always criticize its biases. But newspapers had SPUD that no news media organizations rival today.

Organizations with SPUD tend to produce leaders who are accountable to their members and who are skillful at holding their groups together. If the pastor of a well-functioning church promises to build a playground for the Sunday School, the congregation expects a playground. And if a division arises within the church, the congregation expects the pastor to heal the divide without losing any faction. As the leader of the US, President Trump completely fails on both dimensions of leadership, and I argue that only people who have rarely experienced accountability and inclusiveness would tolerate his style of leadership.

In the talk at CESR, sociologist Nina Eliasoph asked me how conflict figures in the SPUD framework and in my overall story about the hollowing out of democracy. On reflection, I would say the following.

First, I do not treat conflict as definitive of politics. Some politics is win/win and involves people coordinating their behavior to create common goods. The story of Nehemiah in the Hebrew Bible is about the Jews successfully rebuilding Jerusalem with the Persians’ permission. That was a political act of coordination.

On the other hand, politics can definitely include conflict, which is unavoidable in the long run. The wall the Jews built around Jerusalem also excluded gentiles: a prominent theme in the Book of Nehemiah. Conflict should be included in any account of US politics.

SPUD organizations manage internal conflicts. To get from pluralism to unity in a voluntary group without shedding the dissenters requires dealing with conflict successfully. Traditional SPUD organizations, such as major political parties, unions, and denominations, handled conflict constantly. A Nebraska farmer and a Brooklyn stevedore might have plenty of disagreements, but they had to work out solutions at the Democratic National Convention. The Party was a framework for resolving conflict.

And SPUD organizations and movements usually have external opponents. The farmers and urban workers of the Democratic Party faced Republicans at the ballot box. The Civil Rights Movement rushed to Birmingham, AL, shortly after the explicit racist Sheriff Eugene (“Bull”) Connor had been defeated by a moderate in order to hold nonviolent direct actions during Connor’s lame duck period. They counted on him to respond violently on international television, which would unify their potential allies. President John F. Kennedy told Dr. Martin Luther King at the White House, “Our Judgment of Bull Connor should not be too harsh. After all, in his way, he has done a good deal for civil rights legislation this year.”

In recounting this exchange, King immediately adds, “It was the people who moved their leaders, not the leaders who moved the people.” The people behind and beside Dr. King used SPUD to move their leaders, and that required a skillful heightening of conflict.

Our problem, I argue, is that we lack organizations with much SPUD.

You must be logged in to post a comment.