Alzheimer’s patients have been waiting decades for treatments that can meaningfully improve their lives, and advances in research are beginning to yield results. Last month, Biogen and Eisai announced the results of a Phase III study for lecanemab, a monoclonal antibody treatment targeting certain plaques that form in the brain and are linked to Alzheimer’s. They found that their drug reduced cognitive decline by 27% compared against the placebo.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is scheduled to determine whether the drug qualifies for accelerated approval by January, though this is not the first time it’s been presented such a drug. Last year, FDA granted accelerated approval to Aduhelm, a drug similar to lecanemab. Unfortunately, despite the dedication of scientists at leading pharmaceutical firms and the determination of the FDA, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) appeared unconvinced. In April, they dashed the hopes of patients and families by finalizing a coverage policy that only reimburses treatment costs for patients enrolled in certain clinical trials.

This policy applies to all drugs like Aduhelm, including lecanemab and other similar drugs currently in development. This policy will inhibit access to these life-changing treatments, discourage innovation, and leave underserved communities to suffer a disproportionate share of the burden of this disease. Below we discuss how the policy will ultimately inhibit access and discourage innovation.

Inhibiting Access

The National Coverage Determination (NCD) for “Monoclonal Antibodies Directed Against Amyloid for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease” conditions reimbursement for this new class of treatments on

- participation in a randomized-controlled trial when those treatments have received accelerated approval;

- a CMS-approved prospective study when granted traditional approval;

- or a study approved by the National Institutes of Health.

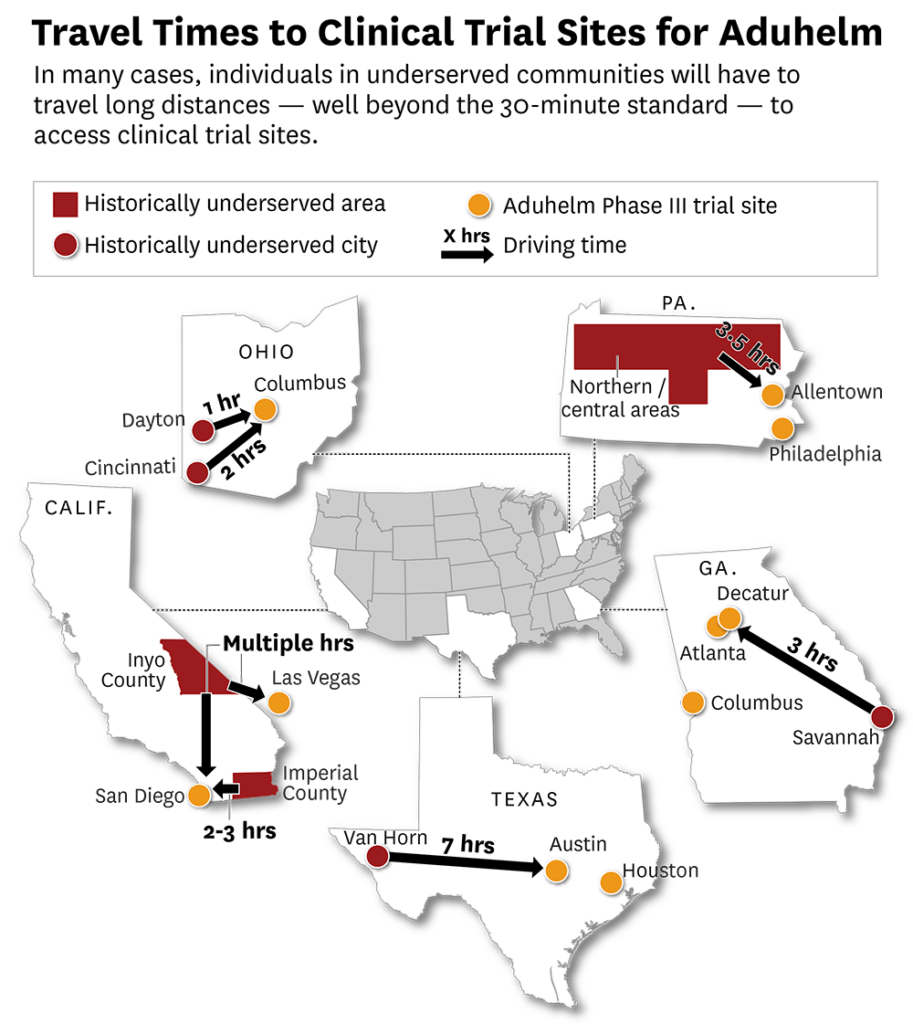

Twenty-three states hosted a Phase III Clinical Trial Site for Aduhelm and in 2019, 1,643 participants were enrolled. Based on an analysis of five U.S. states, we find this requirement severely limits treatment for virtually all Americans living outside of major cities. We used Aduhelm’s Phase III trial study1 to illustrate this point—though they will apply equally to all FDA-approved treatments in this class under current CMS policy.2

A large body of research reflects the inverse correlation between distance and healthcare utilization.3 Based on these studies, several states have considered and implemented a 30-minute travel time standard for access to hospital services.4 Extending this standard to access to the Aduhelm Phase III trial sites means that large shares of populations living well outside major urban centers will struggle to gain access to Aduhelm under CMS’s coverage parameters, and that these problems burden populations that are already disproportionately impacted by Alzheimer’s.

Ohio | Ohio is expected to have 250,000 Alzheimer’s patients by 2025, up from 220,000 in 2020.5 Per capita Medicare payments for beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s in the state exceeded $28,000 in 2018, compared with $10,814 overall.6 There is a high concentration of Hispanics suffering from Alzheimer’s in the Dayton area, and hour away from The Ohio State University Medical Center in Columbus, which hosted a Phase III clinical trial site for Aduhelm.

Residents of Cincinnati must travel two hours to reach Columbus, though one Ohioan had to travel much further. He had moved from Nevada and was participating in the trial through a location in Las Vegas. He found Aduhelm so valuable that he was willing to travel to Las Vegas twice a month. When he was off the treatment, he was liable to believe he was still working, expecting clients to appear in his house, believing he was late for speaking engagements, and attempting to leave the house in the middle of the night in his pajamas or attempting to enter his neighbors’ homes on accident. His wife expressed frustration with CMS’s decision, highlighting the challenges with merely getting into a trial, including numerous tests and qualification criteria that need to be satisfied. She fears her husband will need to be hospitalized or institutionalized without treatment. While the Ohio State University Medical Center hosted a Phase III trial for Aduhelm, there are currently no trial sites for the medicine in the state. The nearest one is in Tennessee.7

Texas | The situation is similar in other states we studied. Within three years, Texas will have an estimated 490,000 citizens living with Alzheimer’s.8 These patients are markedly more expensive to care for than patients who do not have Alzheimer’s. Per capita Medicare payments for beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s in the state exceeded $32,000 in 2018,9 compared with $12,437 per Medicare beneficiary overall.10 There is a high concentration of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in Texas, particularly in Dallas and Austin and along the border with Mexico. Trial sites are in Houston and Austin, which would require many patients to travel across the state to gain access. A resident of Van Horn, TX, for example, would need to drive almost 7 hours to reach a trial site in Austin.

Georgia | Georgia will have approximately 190,000 Alzheimer’s patients by 2025, up from 150,000 in 2020. Per capita Medicare payments for beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s in the state exceeded $26,000 in 2018, compared with $10,684 overall. Atlanta, Columbus, and Decatur all hosted a Phase III clinical trial site. While there is a large share of Hispanics with Alzheimer’s who may be able to access the trial site in Columbus, a substantial number of Black individuals further east in the state would have had a harder time reaching a clinical trial site. For example, individuals residing in or around Savannah would need to travel 3 hours by cars to Decatur to access a trial.

Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania’s patient population will grow to 320,000 over the next 3 years, up from 280,000 in 2020. Per capita Medicare spending for beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s exceeded $28,000 in 2018, compared with per capita spending of just over $11,000 overall. Allentown and Philadelphia both host a Phase III clinical trial site for Aduhelm. Hispanics residing in northern and central Pennsylvania appear to be disproportionately impacted by Alzheimer’s and may attempt to access the trials through Allentown. Some of these patients would need to drive 3.5 hours to access this site.

California | California will bear the greatest disease burden of the states we analyzed, with 840,000 people projected to be living with Alzheimer’s in the state by 2025, up from 690,000 in 2020. Per capita Medicare spending for beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s approached $36,000 in 2018, compared with per capital spending of $13,151 overall. While California is home to more Alzheimer’s patients than any other state, the population is not evenly distributed, with select segments of the state disproportionately impacted. Imperial County (near the Mexican border) and Inyo County (near the border with Nevada) have the highest rates of ethnic minorities suffering with Alzheimer’s and related dementias in the state, at 9.1% and 8.3% respectively. Individuals living in Imperial County would find the closest testing center in San Diego, which could be a 2-3-hour drive. Individuals in Inyo County would have a multi-hour drive to a test center located in Las Vegas or Los Angeles, depending on where in the county they reside.

These five states illustrate the fact that, in many cases, individuals in underserved communities had to travel long distances, well beyond the 30-minute standard, to access clinical trial sites for Aduhelm. Many patients will even have to travel out of state to access a trial site; twenty-seven states lacked a Phase III site for Aduhelm. Usually, approval eliminates these barriers because patients no longer need to report to trial sites to access treatment. Unfortunately, CMS’s restrictive coverage decision ensures these barriers will persist. Many of these patients reside in rural areas, which already suffer a disproportionate burden of disease relative to their urban counterparts. Additionally, women, African Americans, and Hispanics are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s and are therefore disadvantaged most by CMS’s restrictive coverage policy.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

Discouraging Innovation

Aduhelm was the first monoclonal antibody treatment approved to treat Alzheimer’s and several similar drugs in the pipeline suggest the dawn of an exciting new paradigm for Alzheimer’s treatment. Unfortunately, Medicare’s coverage determination restricts coverage for not just Aduhelm, but for all anti-amyloid therapies, even those yet to be approved. Even if one agrees with Medicare’s position that the evidence supporting Aduhelm’s therapeutic benefit is inconclusive and that the risks may not outweigh the benefits, such a conclusion does not warrant blanket noncoverage of the full class of treatments It is worth noting that Medicare’s mandate does not include assessments of safety and efficacy, that responsibility is vested in FDA. However, innovators deserve de novo review of their products based on the evidence they develop to justify coverage and should not be penalized for missteps Biogen may or may not have taken in designing and executing their clinical trials.

Medicare’s NCD has already had real world impacts on research and innovation for Alzheimer’s treatment. Shortly after the final NCD, Biogen announced that it would cancel its observational ICARE AD trial, which would have collected real-world data on Aduhelm’s use in the U.S. This data may have been interesting to Medicare, but its coverage decision means that the study will not proceed.11 Meanwhile, while Roche never committed itself to pursue accelerated approval for its Alzheimer’s drug, the company committed to deliver two large robust studies that are run to the end in its wake. Other companies have postponed submission of accelerate approval applications in the wake of Medicare’s decisions.12

Importantly, the decision has spooked providers, whose willingness to allow their patients to participate in clinical trials is vital. A survey of 81 U.S. based neurologists found that 52% were not likely to allow their patients to enter a trial.13 While recklessness is not appropriate in the development of medication, this heightened degree of caution will delay patient access to new medications to treat a disease which suffers a paucity of options.

Additionally, it is important to remember that CMS sets the tone for other payers and providers in the healthcare system. Following the agency’s lead, United Healthcare, the nation’s largest private insurer, issued a coverage policy nearly identical to that issued by the agency.14 This further restricts the ability of patients who could stand to benefit from the treatment to be able to afford its costs. Similarly, several major hospital systems including the Cleveland Clinic and Mount Sinai have declined to provide the medicine to patients, though these moves preempted Medicare’s coverage determination.15

Underserved Communities

In one of his first actions after assuming office, President Biden signed an Executive Order of Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. This Order instructs the government to advance equity for the underserved and requires agencies to audit their policies to ensure that they promote equity and report findings to the Office of Management and Budget. Unfortunately, CMS’s coverage policy for Alzheimer’s treatments like Aduhelm does not comport with the Order. The policy makes it difficult for individuals from these communities to access reimbursement for these treatments and requires individuals in rural communities to drive multiple hours to access a treatment site.

The states assessed in the inhibiting access section face numerous challenges relating to social determinants of health, with African American and Hispanic patients having a distinctly worse health profile based on measures of self-rated health quality and measures of physical and mental distress.16 There are substantial differences between counties with the highest and lowest prevalence of Alzheimer’s among African Americans with respect to environmental risk factors. In counties with the highest disease prevalence, 54.9% of respondents reported access to exercise opportunities, compared with 83.4% for those in counties with the lowest prevalence, according to a 2020 study published in Neurology.17 These disparities also existed for Hispanics, though they were less pronounced. The study also found higher food insecurity in counties with higher disease prevalence and lower educational attainment.

Additionally, with respect to Hispanics, half the population in counties with the highest disease prevalence lives in rural areas compared with just over a quarter in counties with the lowest prevalence.18 A study published in JAMA noted that rural Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s spend more time in nursing homes, less time in the community, and have shorter survival than their urban counterparts.19

The NCD attempted to address these disparities by requiring the clinical trials associated with these drugs to enroll participants that reflect the overall demography of the disease.20 While well meaning, such a requirement is impracticable and may even place the drug further beyond the reach of patients who need it most. Several commenters on the proposed NCD highlighted the geographic challenges these populations face in accessing trial sites.21 Even in areas with large Hispanic populations, clinical trial enrollment doesn’t always reflect the broader population.22 Factors driving this are numerous, including lack of trust in the healthcare system, lack of scientific understanding, or fear about costs.23 The result of the diversity requirement when compared with these challenges is that running trials will be more difficult and more resource intensive, and that fewer trials will meet the requirements for the drug to gain Medicare coverage. This will further limit availability of these drugs, particularly for underserved communities.

We remain skeptical that CMS’s coverage decision is appropriate for Aduhelm, particularly considering that the agency justified the decision based in part on safety concerns, despite those considerations being vested in FDA and its decision to grant Aduhelm accelerated approval. However, even if one believes there is merit in CMS’s coverage policy for Aduhelm, similar treatments should not face coverage restrictions based on evidence generated by a competitor. Unfortunately, CMS’s coverage policy currently precludes this. Given lecanemab’s promising results, should FDA approve this and monoclonal antibody drug for Alzheimer’s, CMS may need to update its coverage policy, requiring a bureaucratic process that will delay patient access to the medication until the revision is issued. CMS should preemptively walk back its restrictive coverage policy to avoid this unnecessary delay.

Conclusion

The pharmaceutical industry is on the cusp of meaningful breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s treatment with the potential to transform care. Unfortunately, at this time of great promise, CMS used data generated by a single medicine to create a restrictive policy that will apply to all such future treatments. This makes it harder for people with Alzheimer’s to access treatment—especially for those living in rural and underserved communities—discourages innovation, and prolongs patients’ wait for novel Alzheimer’s treatments. The policy ultimately flies in the face of the Biden Administration’s commitments to promoting equity and supporting racial and ethnic minorities, who bear a disproportionate burden of this disease.

CMS should stick to the business of examining medical necessity—its remit—and allow the FDA to make safety and efficacy determinations. It also should immediately revise its coverage policy so that it only applies to Aduhelm, thereby allowing drugs deemed safe and effective by FDA to be covered. That way, effective drugs will not be out of reach for patients waiting on CMS to complete a cumbersome regulatory process to cover a newly approved, effective treatment. Alzheimer’s patients have waited decades for effective treatments to become available, and they do not have the benefit of time.

Joe Grogan is a nonresident senior fellow at the Schaeffer Center and founder and owner of Fire Arrow Consulting, specializing in healthcare and life sciences consulting services.

References

- 221AD302 Phase 3 Study of Aducanumab (BIIB037) in Early Alzheimer’s Disease – Full Text View – ClinicalTrials.gov

- Unless otherwise indicated, data for selected states comes from Place and Brain Health Equity – Us Against Alzheimer’s (brainhealthdata.org)

- Geographic Access to Hospital Care: A 30-Minute Travel Time Standard (wrlc.org)

- Ibid.

- Brain Health Data op cit.

- Custom State Reports op cit.

- ‘It just was the only hope’ – Alzheimer’s patients protest narrowing access to expensive dementia drug – cleveland.com

- alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Ibid.

- Custom State Reports | KFF

- Biogen terminates an Aduhelm study in Alzheimer’s (fiercepharma.com)

- Lilly and Roche learn from Biogen’s mistakes | Evaluate

- Neurologists shun Biogen’s Aduhelm even in clinical trials (fiercepharma.com)

- UnitedHealthcare’s coverage for Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm (fiercehealthcare.com)

- NYT: Cleveland Clinic, Mount Sinai won’t prescribe controversial Alzheimer’s disease drug Aduhelm | Fierce Healthcare

- Urban_UsA2 Brain Health Equity Report_11-15-20_FINAL.pdf (usagainstalzheimers.org)

- Dhana K, Evans DA, Rajan KB, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Healthy lifestyle and the risk of Alzheimer dementia: Findings from 2 longitudinal studies. Neurology. 2020 Jul 28;95(4): e374-e383. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009816. Epub 2020 Jun 17. PMID: 32554763; PMCID: PMC7455318.

- Urban op cit.

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2772022

- NCA – Monoclonal Antibodies Directed Against Amyloid for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (CAG-00460N) – Decision Memo (cms.gov)

- Ibid.

- In Texas, a bold plan to diversify Alzheimer’s research takes shape – STAT (statnews.com)

- Ibid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.