Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently released a secret shopper report on sales of non-compliant health coverage. GAO conducted a series of undercover phone calls to insurance companies, agents, and brokers posing as a consumer with a pre-existing condition. Out of 31 calls made by the GAO secret shopper, ten calls involved sales representatives attempting to sell non-compliant coverage. In eight of those calls (over a quarter of total calls), sales representatives engaged in false or misleading practices of such severity that GAO referred the sales representatives to the Federal Trade Commission for further investigation. These problematic calls resulted in the sale of non-compliant health coverage that would not cover the consumer’s pre-existing condition, despite the sales representatives’ assertions to the contrary. Further, unlike other recent secret shopper analyses (including our own), GAO was able to actually purchase products, allowing review of policy contracts and shedding additional light on what consumers may experience when shopping in this market. Their report underscores three key themes: misleading information is shockingly prevalent, a wide variety of junk plans are sold and may frequently be bundled together, and fixed indemnity plans appear to play a large role.

GAO Found Widespread Problematic Behavior

GAO conducted 31 calls in five different states from November 2019 through January 2020. They used internet searches for “affordable health insurance” or “cheap health insurance” to create a call list of agents and brokers. During the calls, they portrayed themselves as consumers with diabetes or heart disease, seeking a health plan that would cover their pre-existing condition.

In 21 of the secret shopper calls, the broker pointed the consumer towards an ACA-compliant plan. For the remaining 10 calls, sales representatives steered the consumer towards a non-compliant product (or, usually, a group of non-compliant products). During two of those calls, the sales representative did not make statements that GAO classified as misleading, although GAO concluded that the sales representatives were not completely forthcoming about the nature of the coverage. The remaining eight calls, which accounted for over a quarter of the covert calls made, resulted in the sales representatives using potentially deceptive and misleading marketing tactics, including assuring customers that pre-existing conditions would be covered or overstating the terms of the coverage.

Once the undercover GAO shopper had purchased the product, plan documents were made available and GAO was able to compare the fine print of the plan to the discussion during the sales call, identifying a wide range of problematic claims. These fraudulent statements included:

- reassuring the consumer that pre-existing conditions would be covered when they, in fact, would not be,

- describing coverage as part of a comprehensive single product when in actuality it was a number of different products (none of which were major medical insurance),

- relaying to the shopper that they would receive benefits that were not encompassed in plan documents, and

- withholding information about limits and caps on their coverage.

For example, in one call a sales representative told the GAO caller, “For all your emergency room and medically necessary services, you qualify at 100 percent coverage, no deductible. That’s all through your local hospitals there.” However, plan documents revealed there was no coverage for emergency room services in any of the products purchased. During the same call, the sales representative also stated, “Now, medications are $0 to $25 copays, 90-day supply. So – and your medications, taking diabetes meds are 100 percent free for you…You gotta pick them up, but it’s free for you, you don’t pay nothing. It’s a free program. So, zero costs for your meds.” On the contrary, the plan documents showed that the GAO agent had actually been enrolled in two different non-insurance prescription discount programs, the terms of which would not provide the agent with free prescriptions.

In a different call, the sales representative stated, “So… if you’re trying to find the best, most affordable plan, there is a great private option available for you in Florida. It’s going to provide you with unlimited doctor’s visits, diagnostic testing for blood work and lab work throughout the year, medical, surgical, and hospital coverage all with no deductible.” The GAO caller then asked, “Will it cover my diabetes and everything? My insulin?” To which the sales representative responded, “Yes, absolutely. So, with this policy, with your medications, all of those will be covered up to the first 80% of your generic and name brand prescriptions.” The GAO shopper then asked again if the plan would cover his diabetes and insulin. The sales representative reassured him saying, “Yes. Absolutely. Because you have that prescription coverage in there…” But, after purchasing, the plan documents explicitly stated that pre-existing conditions – such as the caller’s diabetes – and prescription drug cost were not covered by the plan the sales representative sold the caller. (Partial audio recordings of some calls are available on GAO’s website.)

These findings add to the growing body of work that notes similar and extensive problems with non–compliant plans.

The Frequency of Misleading and Deceptive Marketing Tactics is Startling

Out of the 31 phone calls, GAO felt compelled to refer 26% of their contacts to an enforcement agency, the Federal Trade Commission. While the report is careful (and correct) to note that the results cannot be generalized to the market as a whole, the findings make clear that it is extraordinarily easy for consumers to encounter information that is intended to mislead.

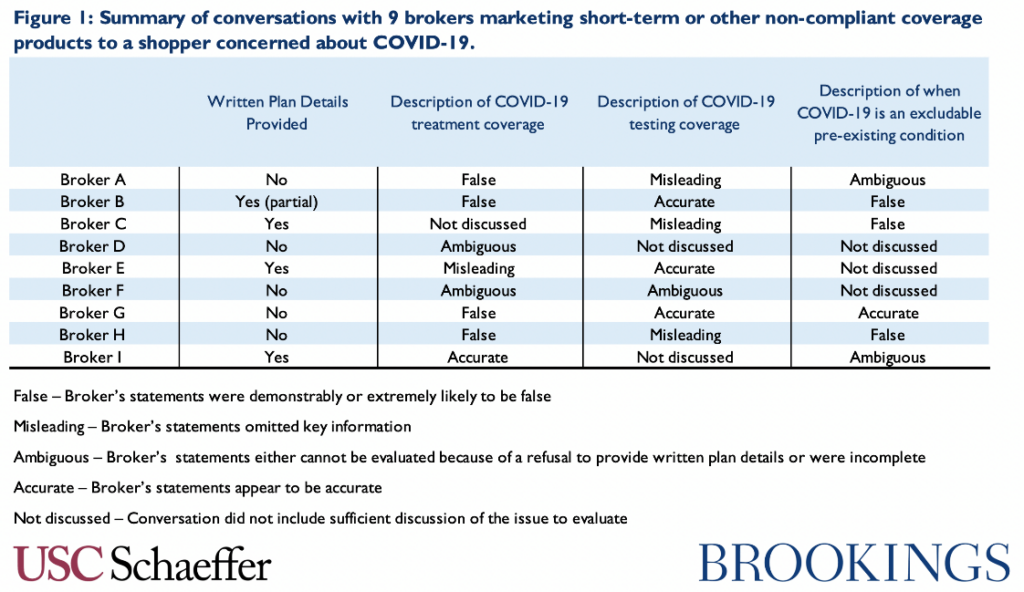

This is consistent with our experience: in late March 2020 as COVID-19 cases began to rise in the US, we similarly made secret shopper calls posing as an uninsured consumer with concerns about COVID-19. We contacted nine brokers across the country in order to inventory marketing practices of short-term or other non-compliant coverage products during the pandemic. We encountered false claims by sales representatives regarding the plan’s coverage for COVID-19 treatment or whether COVID-19 is an excludable pre-existing condition in five of our nine calls, and the other four calls included claims about treatment, testing, or exclusions that we considered at least ambiguous. Figure 1 summarizes our calls.

Similarly, a secret shopper study conducted by researchers at Georgetown University on short-term insurance plans in eight states found that short-term plans’ marketing tactics can also mislead consumers into a false sense of security as to the amount of coverage they have under these plans. In every state studied, the researchers found that web searches for “cheap health insurance,” “short-term health insurance,” and even “Obamacare” or “ACA plans” most commonly resulted in the searcher being directed to lead-generating websites, where the consumer would put in their information and then be called by a sales representative with a plan that “fit” their needs. These websites rarely provided information regarding plan benefits, cost sharing, or premiums. When the consumer was called by a sales representative, the sales representatives would first ask a series of screening questions about the consumer’s demographics and health history before quickly trying to sell them a plan, often without any written information about what the plan actually covers. Together, these investigations suggest that misinformation is not arising from isolated incidents reflecting a few bad actors, but rather from a pattern of behavior that any consumer is at risk of encountering when shopping for coverage.

A Wide Variety of “Junk Plans” are Sold and Bundling is Common

While both our COVID-19 study and the Georgetown analysis focus on short-term insurance plans, the GAO report shows that the concerns around junk insurance are not limited to short-term plans. Our recent paper takes a deep dive into the market for junk insurance and illustrates the variety of problematic policies that can exist under current rules, such as excepted benefit policies (like critical illness, accident, or fixed indemnity plans), Farm Bureau plans, and health care sharing ministries. Consistent with our findings, GAO’s problematic calls revealed that insurers are exploiting many of these options. In the GAO’s nine completed transactions for non-compliant products, eight included an excepted benefit plan and one was a health care sharing ministry membership. In seven of these cases, the GAO shoppers were sold bundled products with two or more health coverage products. These bundled products, as pointed out in the Georgetown analysis, are common among junk insurance sellers and are made up of multiple non-compliant plans such as hospital-only plans, prescription discount plans, and other limited benefit or indemnity plans. Bundling products appears to allow vendors to evade regulation; in many cases, the exception from regulation is offered to a narrowly defined benefit, but combining multiple products together creates the impression of a full benefit.

Fixed Indemnity Plans are a Prominent Feature of the Market, at Least in These States

Fixed indemnity (also called hospital indemnity or limited indemnity) plans were offered to and ultimately purchased by the GAO secret shopper in at least 4 of their nine transactions. Those plans consistently left the shopper without coverage for their stated pre-existing condition. Indeed, fixed indemnity plans, which make payments on a “per time period” basis, are a problematic and nontransparent form of junk insurance, and the GAO’s report suggests that they seem to be increasingly common. Our recent work on fixed indemnity plans examined a variety of marketing materials associated with these plans. The materials we reviewed seem intended to lead consumers to believe they are a suitable, comprehensive substitute for major medical insurance, and GAO’s work demonstrates that misuse in practice. As the GAO report documents, these sales leave consumers exposed to significant costs with per service benefit limits and low annual or lifetime benefit maximums.

Research Reveals a Clear Need for Oversight

The GAO’s secret shopper results underscore that misinformation or confusion among buyers of non–compliant health coverage is not only the result of failings on the consumer-side, but in many cases reflects ambiguous and fraudulent marketing tactics by the sellers. As the evidence continues to demand further regulation of these markets, we have presented options for policymakers to establish better oversight over these products. There are actions that can be taken at both the federal and state level to protect consumers.

Without federal action, states should have stricter regulatory standards for all types of junk insurance plans, beyond short-term plans. Many states have already taken action to regulate short-term plans, but they have taken fewer steps to regulate other aspects of the junk insurance market. (One notable exception is New Mexico, which is pursuing broad regulations to protect pre-existing conditions and other benefits mandated by the ACA across the market.) Additionally, regardless of what is available for sale, the multiple secret shopper reports show that state oversight of agents, brokers, insurers, and other sales representatives is necessary in order to protect consumers. States directly license and regulate brokers and agents, so they have the ability to establish and enforce disclosure requirements for agents and brokers selling non-compliant plans, similar to rules already in place in Illinois and California.

Similarly, the federal government should exercise tougher oversight of brokers, including web brokers, when possible. For example, the federal government sets standards for agents and brokers that want to sell coverage on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace; the federal government also regulates state-based marketplaces, giving them the authority to increase standards for agents and brokers who work in the federal and state marketplaces. Further, the federal government should tighten definitions of limited benefit policies — including fixed indemnity, accident, and potentially critical illness policies — to restrict markets that are producing junk insurance. Congress can enact new legislative definitions, but even under existing statutes, federal agencies also have the authority to define the features that differentiate limited from traditional coverage.

You must be logged in to post a comment.