Hospitals in Miami produced 13 percent fewer high-quality hospital stays than the U.S. average, while hospitals in Everett, Washington, a city 25 miles north of Seattle, perform over 20 percent better than average on value.

This is according to a new study published in PLOS One and led by experts at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics that leverages measures of quality in care delivery and cost to determine a value index score, and uses this score to measure variation in the value of inpatient care across U.S. regions.

“Improving value in the healthcare system has been at the center of an array of reform initiatives over the past few years,” said John Romley, the lead author on the study. “But before this study, a practical measure of value in care delivery hadn’t been developed. Our quantitative measure will allow policymakers to better compare how regions across the U.S. are performing.” Romley is an associate professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy and the USC School of Pharmacy and at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

Quality – Cost = Value

It has been well documented that healthcare cost and use vary considerably across the U.S. Variation in quality of care delivery, though harder to measure, has also been documented.

Intuitively, measures of quality and cost inform value in care delivery.

Yet, putting a number on value is more complicated. As the authors point out, if hospitals in region A have better quality but higher cost than those in region B, either one of these regions could rank higher on value, depending on the degree to which those variables diverge. Likewise, if quality is higher in region A and costs are the same, one could reach the qualitative conclusion that value in region A is greater than region B, but getting at how much better would still be nebulous.

A Value Index for Inpatient Care Following a Heart Attack

To pinpoint the degree to which value varies across the U.S., the researchers analyzed data on over 33,000 elderly fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who were admitted with a heart attack to 2,232 hospitals in 304 hospital referral regions (HRR) in 2013. HRRs are recognized healthcare markets. Each HRR includes at least one hospital where major cardiovascular surgical and neurosurgery procedures are performed.

The researchers measured the total number of high-quality stays (which they defined as a patient survived for at least 30 days beyond the admission and avoided an unplanned readmission within 30 days of discharge) and measured it against the total cost to each hospital of treating patients, taking into account patient severity and socioeconomic factors as well as hospital characteristics.

Value Across the U.S. Varies Considerably

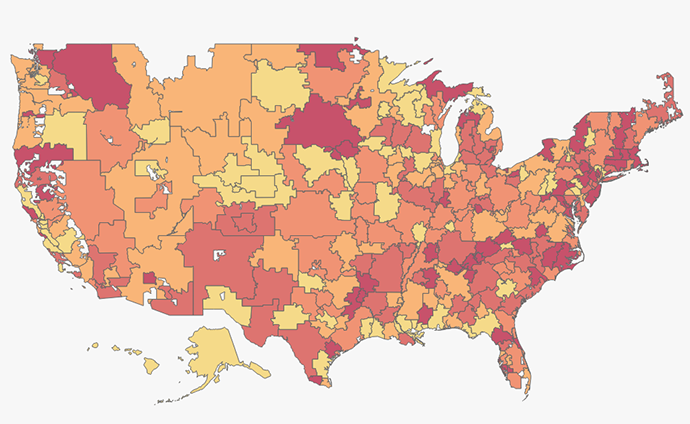

The map above indicates the value of care delivered in each HRR, with the darkest shade representing the highest quintile of value. Hovering over each region will allow you to see the region’s scores on value as well as the breakdown of cost and quality. The score is based off a national average of 100.

Among all HRRs, 71 percent were statistically different from 100. Overall, about one in 8 regions had a value index score greater than 120 (thus delivering at least 20 percent more value than the national average).

Compared to the average, Pontiac Michigan, a small city in Metro Detroit, scored a 127, meaning the hospitals there were able to deliver 27 percent more high-quality stays than other hospitals with similar patients and costs. Just east of Pontiac is Detroit, which scored a 99.

In some areas, hospitals with high-risk adjusted costs also tended to deliver high adjusted quality of care and thus performed well on value. For example, the Atlanta, Georgia hospital referral region had costs 6 percent higher than the national average yet their score on quality was also high, 10 percent above average. Thus, their value index score was 104.

Conversely, some areas with relatively low quality were still deemed high value because of sufficiently low costs. For example, Hartford, Connecticut scored 7.5 percent below the national average on quality. On cost, they were 13.4 percent below the national average. Thus, on the value index they scored 121.

Another way to analyze the distribution of value is to consider the difference between the region that scored at the top 90th percent compared to the region that scored at the bottom 10 percent. Value in care delivery was 54 percent higher for the region whose performance placed them at the 90th percentile compared to the region at the 10th percentile. Hospitals in the median HRR would have to increase their performance by 22 percent to be in the top 10% regions.

In delivering inpatient care for heart attacks, there was more variation in value than in either quality or costs. More than half of regions in the study that performed above average on value were either below average with respect to quality or above average with respect to cost.

Value as an Indicator When Considering Payment, Delivery System Reform

Reducing wasteful spending and improving outcomes are key drivers of payment and delivery system reforms implemented by Medicare and other payers in the last few years. The variability in the value of care documented by this study points to potential opportunities for higher quality, lower costs, or both within the healthcare system.

“Our findings point to the need for more research so policymakers can better understand reasons for variation in value and consider more targeted interventions that appropriately incentivize improved performance,” said Romley.

There are likely lessons to be learned from the practices and cultures of high-performing hospitals, to then be implemented by providers whose value in care delivery lags behind. To this end, as policymakers implement reforms, it is important to think about how you reward and prioritize value.

Coauthors on the study include Erin Trish, Dana Goldman, and Paul Ginsburg of the USC Schaeffer Center, Melinda Beeuwkes Buntin of Vanderbilt University and Yulei He of the University of Maryland University College. The research was supported by the Commonwealth Fund and the National Institute on Aging.