In California, more than 2.7 million adults experienced serious mental illness (SMI) in the past 12 months. These individuals are more likely to experience lost wages, interaction with the criminal justice system, and lower life expectancy.

But, interventions aimed at educational attainment may help mitigate these effects. This is according to research conducted by a team at the USC Schaeffer Center and led by Seth Seabury, an associate professor at the USC School of Pharmacy. Seabury presented the findings to Sacramento lawmakers on May 7 at the Capitol Statehouse at a briefing co-hosted by the Schaeffer Center and the Steinberg Institute.

Mental illness is associated with significant economic and quality of life burdens, but measuring the cost effectiveness of interventions is challenging, explained Seabury. “The benefits are long term and the benefits accrue to different players. Our research aims to quantify the true benefits and cost over the lifetime, so policymakers have a more accurate idea of what is involved.”

About 50 analysts, staffers, and mental health advocates representing federal, state, and local offices attended the briefing, which focused on the devastating impact of serious mental illness in California and the nation.

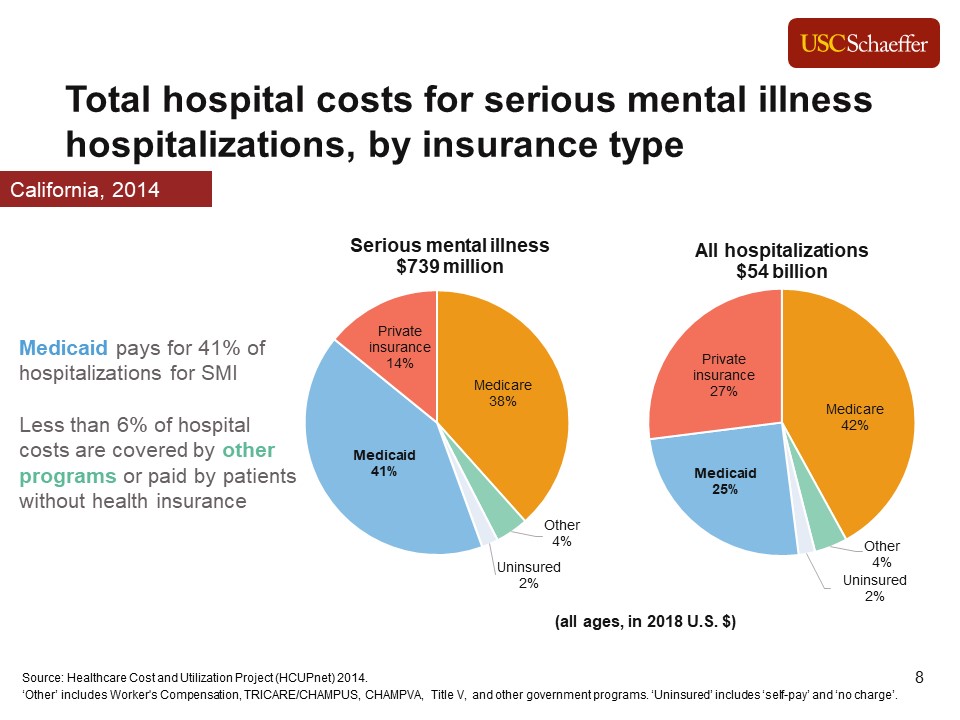

Serious mental illness (SMI) includes conditions like major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Individuals with serious mental illness are associated with higher total hospital costs to Medicaid and are more likely to interact with the criminal justice system.

For example, according to Seabury’s calculations, Medicaid pays 41 percent of hospitalizations for SMI in California.

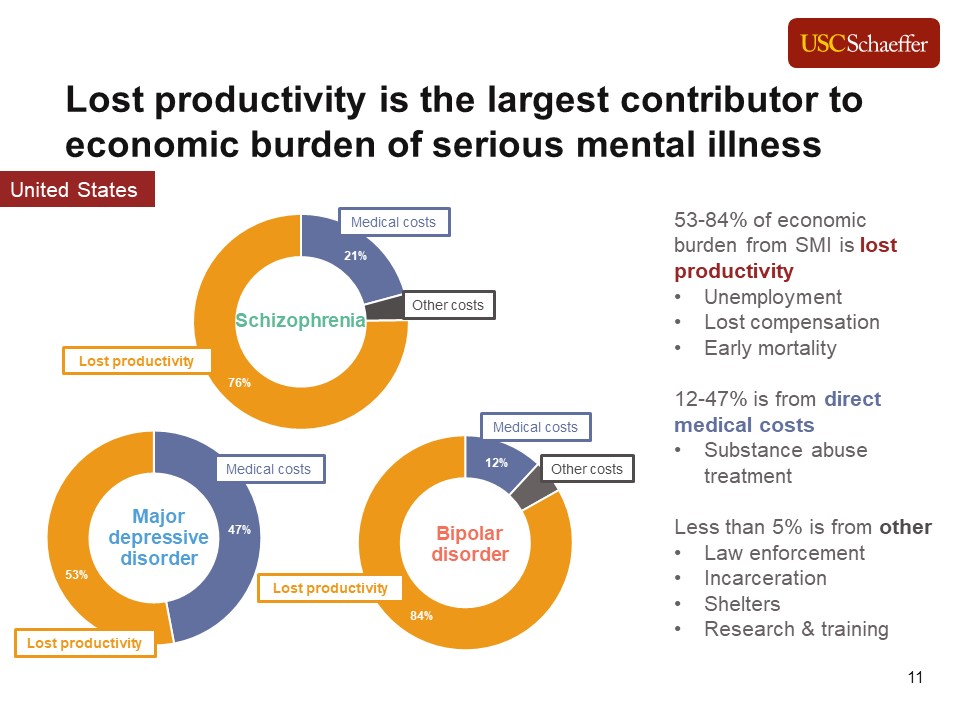

Lost Productivity is the Largest Contributor to the Economic Burden of Serious Mental Illness

Seabury explained that lost productivity accounts for 53 to 84 percent of the economic burden from SMI. This includes things like unemployment, lost compensation, and early mortality. In comparison direct medical costs account for 12 to 47 percent of the economic burden. Less than 5 percent is from other costs, including law enforcement, incarceration, shelters, and research & training.

Interventions Accrue Benefits Over the Course of a Lifetime

Since there aren’t trials or interventions that reliably track individuals over the course of their lifetimes, it is challenging to measure the future value of today’s investments. Seabury and his colleagues used the Future Adult Model, a microsimulation model developed at the Schaeffer Center, to simulate experiences of an individual from age 25 to death. Using the FAM allows researchers to conduct hypothetical experiments and measure how they impact lifetime outcomes.

Higher educational attainment seemed to mitigate some of the burden. For example, people with more than a high school education with SMI averaged $954,000 in lifetime earnings compared to $193,000 for people with less than a high school education with SMI.

Seabury and his colleagues used the FAM to assess what the return would be if everyone with SMI were enrolled in a supported education program. Nationally, the lifetime benefits of such an intervention include one year of increased educational attainment, a reduced economic burden which results in a two-to-one return on investment over the lifetime.

In California, the simulation showed savings of over $900 million over the lifetimes of the roughly 16,600 California 25-year-olds currently living with serious mental illness if an early intervention to support educational achievement were implemented. “That’s a 1.6 rate of return on investment,” Seabury said.

“Think of the cost of intervention as an investment,” Seabury said during the briefing. Interventions that accrue benefits over a lifetime are challenging. “It requires patience, vision, and good measurement.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.