‘Forgotten middle’ Americans face poorer health, worse economic outcomes and lower homeownership rates, along with increased disability in old age.

Lower-middle class Americans nearing retirement age are worse off than their counterparts more than two decades ago, while upper-middle Americans have largely seen their life expectancy and wealth improve. Policymakers, meanwhile, overlook the lower middle group of Americans who don’t qualify for many assistance programs. That’s according to a new study by the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Using data from the Health and Retirement Survey and a microsimulation called the Future Elderly Model, researchers estimated future life expectancy and disability for cohorts of individuals in their 50’s at different times between 1994 and 2018.

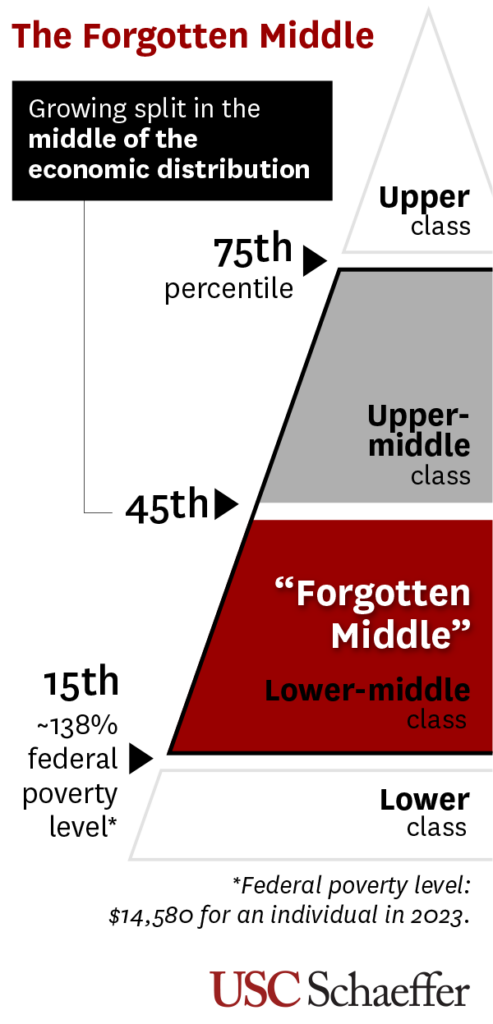

Researchers grouped individuals by economic status: upper, upper-middle, lower-middle and lower. The results, published online in Health Affairs, showed healthy life expectancy at age 60 increased 1.5-2 years for the higher economic groups but was stagnant or decreased for the lower ones. They found a similar pattern when they looked at the number of future life years without disability.

Study authors said the health status at age 50 for both the upper and lower middle has worsened over the past two decades, but health is deteriorating faster for the lower middle. Worsening health includes increased hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease.

“Our findings suggest that today’s lower-middle class will spend a larger proportion of their older life with poor health,” said Jack Chapel, study lead author and a PhD candidate in economics at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “For example, an average 60-year-old woman in the lower-middle in 2018 will reach age 84. We project that almost 40% of her remaining years will be lived with a disability – an increase since 1994.”

The ‘forgotten’ lower-middle increasingly struggles to pay for health care and housing

Study authors say policymakers continue to focus on assistance for the most disadvantaged Americans, while neglecting those just one step up the income ladder. The researchers call this group the “forgotten middle” – overlooked because they don’t qualify for supports such as Medicaid, housing vouchers or food stamps, yet lack adequate resources to cover the increasing costs of healthcare and housing.

Researchers found the combined value of financial and housing wealth and other resources including income, health insurance benefits, and quality-adjusted life-years after age 60 grew 13% for the upper middle group between cohorts. Meanwhile, people in the lower-middle group in 2018 were barely better off – with just 3% growth – compared to their earlier counterparts.

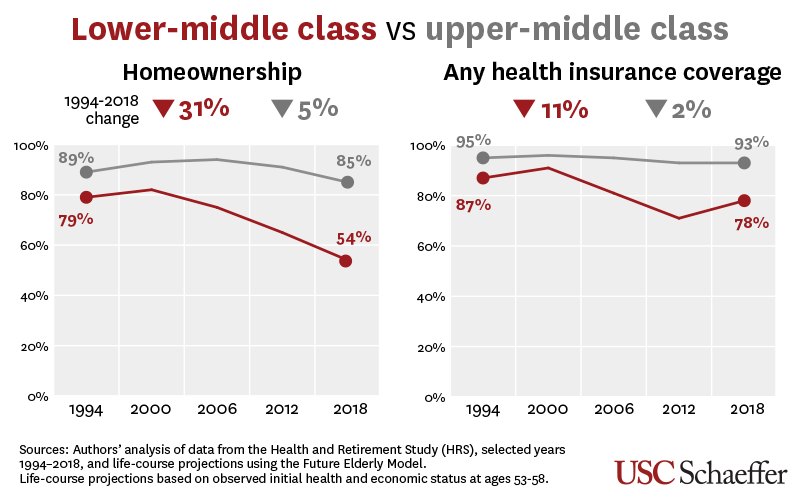

The growing gap was driven by robust growth in private income and housing wealth for the upper-middle group, compared with stagnation in both categories for the lower-middle group, whose reduced economic fortunes included a striking drop in homeownership at midlife. The lower-middle trailed the upper-middle group in homeownership by 10 percentage points in 1994; by 2018, this gap had tripled.

An interactive data visualization with all data the researchers analyzed is available here

“Our study projects lower-middle Americans will spend a longer proportion of remaining life with significant healthcare needs, but with no more economic resources to attend to those needs than similar cohorts had 20 years earlier,” said Dana Goldman, dean and C. Erwin and Ione L. Piper chair of the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy and the co-director of the USC Schaeffer Center.

The study authors said the ripple effect – an overburdened healthcare system, reduced productivity and strained family caregivers – should concern Americans at every income level.

“The public conversation about inequality tends to focus on the challenges faced by only the most vulnerable populations,” said Bryan Tysinger, director of health policy simulation at the USC Schaeffer Center and research assistant professor at the USC Price School. “But our models found that there has been an important divergence in the middle of the economic distribution.”

Researchers point to the improvement of health insurance coverage rates for the study’s lower-middle cohort after implementation of key parts of the Affordable Care Act in 2014 as an example of an effective strategy, while acknowledging the policy change did not offset the losses in employer-sponsored health insurance that disproportionately impacted the lower-middle class.

Additional authors included John W. Rowe, MD, Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the Butler Columbia Aging Center, and the Research Network on an Aging Society.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

You must be logged in to post a comment.